Abstract

Background: Enteral nutrition (EN) intolerance is a common complication in critically ill patients that contributes to morbidity and mortality. Based on the evidence of curing effects of fenugreek seeds in some gastrointestinal disorders, this study aimed to determine the effects of fenugreek seed powder on enteral nutrition tolerance and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients.

Materials & Methods: A randomized, double-blinded clinical trial of 5-day duration was conducted on 60 mechanically ventilated patients divided in 2 groups (n=30). Group 1 was given fenugreek seed powder by gavage, twice a day in addition to routine care, while Group 2 received only routine care. Enteral nutrition tolerance and clinical outcomes were measured throughout the study. Demographic and clinical data were recorded and clinical responses to the primary outcome (enteral nutrition tolerance) and secondary outcome (other clinical factors) were interpreted. Data were analyzed using the independent t-test, Chi-squared test, covariance analysis, and repeated measure ANOVA via SPSS statistical software (v. 20); statistical significance was set at p< 0.05.

Results: Patients who were fed with the fenugreek seed powder showed a significant improvement in enteral nutrition tolerance, as well as some complications of mechanical ventilation for Group 1, as compared with Group 2. The mortality rates were not different between the two groups.

Conclusion: This study shows the beneficial effects of fenugreek seeds on food intolerance in critically ill patients and that the seed powder can be used as an add-on therapy with other medications. Thus, the use of fenugreek seeds to treat mechanically ventilated patients is recommended.

Background

Nutritional support is a right for acutely ill patients and is an essential factor of optimal care in this population 1. Enteral nutrition (EN) correlates with better outcomes and is considered the safest manner. Patient intolerance typically occurs in one-third of the EN cessation time 2. EN intolerance has been reported in up to 60% of patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) 3.

Different methods for assessing nutritional tolerance include monitoring of the gastric residual volume (GRV) and intestinal sounds, and abdominal radiography 4. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) occurs in approximately 59% of mechanically ventilated patients and 80% of patients with increased cranial pressure following head injury 5. Several strategies to prevent and treat DGE include: the use of feeding vs intermittent bolus feeding, prokinetics, post-pyloric feeds, and herbal remedies. The technique of post-pyloric feeds can be challenging. Furthermore, prokinetic agents have cross-sectional effects, including side effects and drug resistance, especially in long-term use 4.

Researchers have found that the health effects of gastrointestinal microbiome modulators (GIMMs) are similar to probiotic therapy. GIMM-induced growth selectively promotes probiotics (live microorganisms that confer a health benefit on the host) 6. Also, instead of lactic acid, it produces short chain fatty acids. Moreover, it is worth noting that short-chain fatty acids, such as propionic acid and butyric acid, play an important role in gut health 7.

A dietitian’s assessment is valuable for critical care outcome but, unfortunately, it is often neglected due to the obvious tendency to gravitate towards the other vital organs 8. Researchers have always been looking for safe and applied methods to treat and relieve these problems. Today, the trend towards the production and consumption of supplemented foods has dramatically grown. Scientists are more concerned about prebiotics than probiotics. Each individual has his/her own microflora, and these bacteria vary from one region of the world to another. Therefore, instead of introducing new probiotic species into the human body, either in pure form or with food, it is better to develop specific probiotics of the digestive tract of that individual. This can be done with the help of prebiotics 910. Protein and caloric goals in EN are clearly superior to parenteral nutrition (PN) when a functional gut is currently present 11.

Based on a long history of use of fenugreek by humans, fenugreek is known to be safe. Moreover, new industrial and pharmaceutical uses have been found for this plant. Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) is a one-year-old aromatic herb of the legume family. Fenugreek seeds contain 45-60% carbohydrates that can act as prebiotics 12131415. There are dietary fibers of fenugreek seeds resistant to digestion in the human small intestine and selectively metabolized by intestinal flora, thereby selectively promoting probiotic growth 16. Dietary fibers of fenugreek seeds increase the bulk of the food, augment bowel movement, and influence digestive enzymes 15.

There is a common incidence of food intolerance in ventilated patients. It seems that by incorporating fenugreek seeds in the diet, patients can improve EN tolerance. Considering the importance of this issue, we decided to study the effects of fenugreek seeds on EN intolerance and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients.

Methods

The clinical trial group led two parallel randomized studies. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Sabzevar University approved the protocol of the present study, including written, informed surrogate consent (Code of ethics: IR.MEDSAB.REC.1394.128). Sixty patients were recruited from April 2015 to June 2016 at two intensive care unit (ICU) centers (Dr. Shahid Beheshti’s unit and the Mohammad Vasei Hospitals, Sabzevar, Iran).

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

Exit criteria during the study included:

All screenings were performed daily by the investigator. Conscious consent was obtained from all patients who had inclusion criteria, and all the risks and benefits were explained. Each sample, with the help of random numbers, was placed in one of the 2 groups and the same patient was placed in the opposite group. Sampling continued up to the desired sample size. Demographic information and base-line clinical data (GRV, clinical profile, medical history, and APACHE II score) were collected on the first day of admission. Patients were equally divided between the 2 groups (Table 1). The nurses, doctors, students and other personnel were blinded to this study. Group 1 received 3g fenugreek seed powder twice a day via nasogastric tube, while Group 2 only received the routine care. The first gavage of fenugreek seed was performed within 24 h of admission.

To achieve a double-blinded study, a code was given to all sampler dishes. The nasal gastric tube (NGT) of samples was No. 16. NG tube was attached to a 60-mL syringea then gastric contents were aspirated and volume was recorded. Samples were gavaged under the influence of earth gravity (within 10-15 minutes at a height of 12 inches height above the gastric level). During lavages, the gavaged patient’s head was elevated >35º from the bed and this position was maintained until 1 hour afterwards. After pouring warm soup into the gavage dishes, 3 g of fenugreek seed powder was added into the sample dishes of Group 1 12thand 18th h (without the presence of other reagents. Adding fenugreek seeds did not change the color and appearance of the soup.

The primary outcome was EN tolerance. Common manifestations of EN intolerance, including delayed gastric emptying (DGE), gastric reflux, diarrhea (three or more loose stools per 24 h), and constipation (no defecation for 3 consecutive days), were recorded for 5 days. The GRV has been used as an indirect surrogate of gastric emptying (Anon n.d.). Secondary outcomes, including frequent development of respiratory aspiration, mortality rate, duration of mechanical ventilation, length of stay in hospital, length of stay in ICU, clinical status of patients and hospital charges, were recorded until discharge or death of patients.

The reasons for using fenugreek seed in this study was that it can change flora (even in small amounts) and it is a native plant that is physiologically compatible with the body of the indigenous people of this region. Besides the fact that fenugreek is a rich source of calcium, iron, and vitamins A, B, and C, it is also a good source of essential amino acids, especially leucine, lysine, and total aromatic amino acids. Fenugreek seeds contain 20-25% protein, 6-8% oil, 45–50% dietary fiber, and 2–5% steroidal saponins. It is also effective in the digestion and treatment of hypercholesterolemia and hyperglycemia 161718. Fenugreek seeds were prepared from the Sabzevar region, then washed with water and air-dried for 24 h. The seeds were grinded into powder with a Wiley mill (Thomas Scientific, Philadelphia, PA, USA).

Results

A total of 116 patients were screened based on initial entrance and exclusion criteria of the study. Of the 60 patients (100%) who were randomly selected, 18 patients (30%) were excluded during the study. Out of these 18 patients, 10 (55.55%) and 8 (44.44%) were in Group 2 and Group 1, respectively. Of the 10 excluded patients in Group 2, 3 patients (27.2%) died in the first 48 hours of ventilation, 4 (40%) did not have surrogate consent to continue the study, and 3 (27.2%) were unlikely to need intubation for at least 48 h. Out of 8 excluded patients in the group 1, 4 (50%) died in the first 48 hours of ventilation and 4 (50%) were unlikely to need ventilation for at least 48 hours.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0, Somers, NY, USA) software was used for statistical analysis. First, the normal distribution of variables was investigated using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Regarding the normal distribution of GRV, the Student’s t-test was used to compare the mean GRV. The Mann–Whitney U test (non-Gaussian distribution) was used for continuous variables, such as the mean age (P=0.25), mean sex (P=0.120), mean APACHE II score (P=0.65), and reasons for admission to the ICU (P=0.120). There was no significant difference between the 2 groups in the first admission (Table 1).

| Variables | Group 1 | Group 2 | P-Value | |

| Gender | Male | 12(40) | 19(63.3) | 0 .120* |

| Female | 18(60) | 11(36.6) | ||

| Age (mean± SD) | 54.366 ±19.18 | 59.533 ±17.371 | 0.251*** | |

| Apache II score (mean± SD) | 22.7± 7.5 | 23.7± 8 | 0.45** | |

| ReasonsICU | Head trauma | 16(53.3) | 10(33.3) | 0.792* |

| Multi-organ trauma | 9(30) | 7(23.3) | 0.771* | |

| Diabetes disease | 10(33.3) | 21(70) | 1.00* | |

| Respiratory failure | 6(20) | 3(10) | 0.27* | |

| Cardiac pathology | 19(63.3) | 17(56.6) | 0.792* | |

| Neurological pathology | 6(20) | 5(16.6) | 0.89* | |

| Digestive pathology | 26.66 | 413.3 | 0.89 * | |

| Glandular pathology | 1(3.33) | 0 | 0.89 * | |

| Infectious pathology | 3(10) | 2(6.66) | 0.89* | |

| Length of stay in hospital (day) | 24.1± 5.6 | 27.4± 6.6 | 0.238*** | |

| Length of stay in ICU (day) | 14.2± 4.8 | 17.6± 6.7 | 0.041*** | |

| Intestinal sounds | 10.11 ±18.06 | 20.20 | 0.414** | |

| Smoking | 9(30) | 7(23.3) | 0.792 * | |

| Addiction | 13(43.3) | 11(36.6) | 0.792 * | |

| Stimulant drugs gastric | 13(43.3) | 11(36.6) | 0.792 * | |

| Sedative medications | 15(50) | 14(46.6) | 1.00 * | |

| GCS | 7.6±2.06 | 8.4±2.35 | 0.275*** | |

| Volume of nutrition | 154.66 ±53.54 | 149.666± 41.292 | 0.724*** | |

| Degree Ps ventilator | 9.50 ± 0.572 | 9.766± 0.626 | 0.094*** | |

| Degree PEEP ventilator | 6.40 ± 0.93 | 1.00± 6.50 | 0.694*** | |

| % mouth hygiene | 0.932± 6.40 | 2(6.66) | 0.64* | |

| Oral hygiene (poor) % | 3(10) | 29(96.66) | 0.3* | |

| Diarrhea caused by ICU stay | 27(90) | 6(20) | 0.4* | |

| Respiratory aspiration% | 1(23.3) | 1(3.3) | P=0.005**** |

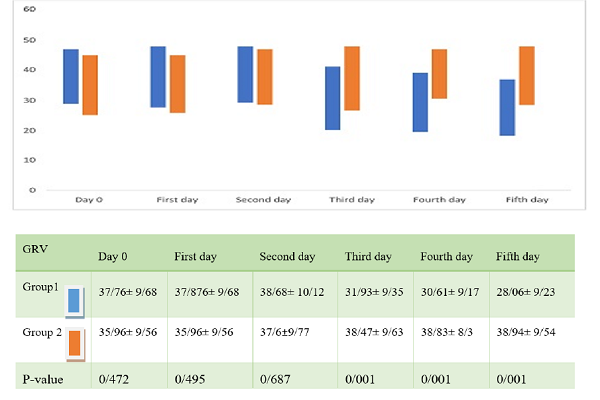

Comparison of the mean GRV, using an independent t-test, for the 2 groups at admission time and the first day showed that there was no significant difference between the groups (p >0.05). However, comparison of the mean GRV in the 2 groups from the 3rd-5th day of the study, using covariance analysis, showed a strong decreasing trend in Group 1; one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between the two groups (p=0.001). After 5 consecutive days of study, it was observed that the mean GRV of Group 1 was significantly different (p=0.001) from that of Group 2 (Figure 1).

In the 2 groups from the 3rd-5th day of the study, using covariance analysis, there was an observed decreasing trend in Group 1; one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between the two groups (p=0.001). In the 5 consecutive days after the study, for Group 1, the difference in mean GRV was significantly (p = 0.001) different compared to that of Group 2 (Table 2).

| Mean GRV at five consecutive days of study | Degrees of freedom | Average squares | F | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 2/506 | 1331/014 | 463/025 | 0/001 |

| Group 2 | 2/924 | 66/759 | 105/510 | 0/784 |

| P-value | 2/633 | 13/602 | 7/819 | 0/001 |

The secondary aim included the evaluation of the average number of days spent in the ICU [Group 1: 14.2±4.7 vs. Group 2 [17.6±6.5, p=0.028], length of stay in the hospital [Group 1: 24.1±5.6 vs. Group 2: 27.4±6.6, p=0.041], rates of diarrhea [Group 1: 1 (3.33%) vs. Group 2: 6 (20%), p=0.04], and cases of respiratory aspiration (33.3% vs. 3.3%, p=0.005). These variables were higher in Group 2. The duration of mechanical ventilation (16.06±4.81 vs. 20.26±6.05, p=0.64) was not different between the groups. No side effects were observed that were attributable to the use of fenugreek seeds. Specifically, no cases of diarrhea related to the ICU and 3 cases of constipation were observed in Group 1, while both cases were significantly increased in group 2 (P=0.001) (Table 3Table 4).

| Source changes | Degrees of freedom | Average squares | F | P-value |

| Effect of group on first day | 1 | 0/026 | 0/0005 | 0/990 |

| Effect of group on second day | 1 | 408/37 | 8/76 | 0/004 |

| Effect of group on third day | 1 | 959/07 | 9/29 | 0/003 |

| Effect of group on fourth day | 1 | 1224/60 | 9/91 | 0/002 |

| Effect of group on fifth day | 1 | 1224/05 | 9/85 | 0/002 |

| Variables | Group 1 | Group 2 | P- Value |

| Stay in ICU (day) | 14.2± 4.7 | 17.6± 6.5 | 0.028*** |

| Duration MV (day) | 16.06 ± 4.81 | 20.26 ± 6.05 | 0.64*** |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 4(13.3) | 0.001* |

| Respiratory aspiration of fifth and sixth days | 10(33.3) | 1(3.3) | 0.005**** |

| Intestinal sounds (mean± SD) | 20.20 | 18.10 | 0.020** |

| Constipation | 3(10) | 21(70) | 0.001* |

| Normal defecation | 27(90) | 5(16.7) | 0.001* |

Discussion

The results of this study showed that fenugreek seeds have favorable effects on food tolerance and were associated with better outcomes in patients with enteral nutrition intolerance. These findings were based on the findings of other scientists on the use of fenugreek for treating gastrointestinal disorders and in cooking 19. Furthermore, the relationship between elevated blood glucose and deleted gastric emptying led to a study, conducted by Kaur and et al. (2016), confirming the results of the previous article 20.

This study on 60 Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients demonstrated that simultaneous use of fenugreek seeds and metformin tablets for 12-week duration improved fasting blood glucose (FBS) and GI side effects of metformin (such as heartburn, nausea, abdominal pain, bloating and diarrhea), as compared to those in the control group who received only metformin (p< 0.05) 20. Fenugreek seeds induced selective stimulation of useful intestinal microflora, improved and adjusted the microbial microflora ratio of the intestine, increased mucosal secretion, and decreased GI complications of metformin tablets.

In a study conducted by Burton et al. (2015) on 10 Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients who had signs of side effects of metformin, for two-week duration, each patient was given 500 mg metformin plus GIMM, or the same dose of metformin plus placebo 6. Two weeks after the end of the first phase, GIMM was given to those who used the placebo and vice versa. For evaluation of digestive symptoms after each phase, an IBS questionnaire was completed by the patients and the FBS was checked with a glucometer. It was found that GIMMs significantly reduced GI complications of metformin and increased the metformin tolerance. FBS was also significantly reduced in patients taking GIMM and metformin 6. Since GI complications of metformin may be due to an adjustment of flora in the GI, the results of this study are consistent with Burton’s study.

In a study by Helmy et al. (2011), the addition of extract, powder and oil of fenugreek (by gavage to the stomach of a mouse) reduced GRV (p<0.01) and increased food intake (p<0.01), and food efficiency ratio (p<0.001), as well as weight gain (p<0.05) 21. The results of the above study are consistent with those of our study. Platel et al. (2003) reported that fenugreek seeds stimulate and activate digestive enzymes in the mouse digestive system. The results showed that 2 g of fenugreek seeds had the highest stimulatory influence (80%) on bile acid secretion compared to the control group. In a single dose (0.5 g/kg) of fenugreek seeds, there was a 35% increase in bile acid secretion and 44% increase in bile flow. Fenugreek seeds increased the activity of pancreatic lipase by 43% compared with the control group. Chymotrypsin activity also increased by 43%. However, there was a decrease in pancreatic amylase, trypsin, and acid phosphatases, and the alkaline state of the intestinal mucosa 22. The pancreatic enzymes strengthen muscle contractions thus the time of emptying the stomach/intestine decreases. The results of their study are consistent with those of our study.

In a study by Ghochae et al. (2013), ginger extract was used to treat mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU, and then the amount of EN tolerance and GRV were measured. It was found that the GRV in the ginger group was lower than that of the placebo group, and the EN tolerance was higher than that of the placebo group 23. Furthermore, ginger and fenugreek seed are prebiotics and can benefit the host 24. The results of their study are consistent with ours. However, ginger should be used with caution in mechanically ventilated patients since these patients are susceptible to mucosal lesions and ulcers 25. Indeed, in the Ghochae study, patients with GI ulcers were excluded.

Fenugreek seeds are not only contraindicated in these patients, but also have beneficial nutritional effects, and can control blood glucose and lipids262728293031. In the present article, none of the participants had a residual volume of more than 200 ml and the nutrition of patients was evaluated according to the instructions. Our study showed a decrease of GRV along with decrease of vomiting or aspiration. In a study by Vazzques-Sandoval et al., 205 patients were divided in 2 groups (GRV group and non GRV group). In the GRV group, had feedings held if a GRV were > 250 mL. Aspirations in the GRV group were not statistically different from apposite group that did not have GRV checked 32. Nutritional support is an essential factor in the care of the critically ill. The main cause of discontinuation of nutrition in ICU patients is the increase of GRV 333435. Therefore, it is recommended to use fenugreek seeds along with other medicines and therapeutic measures to improve nutrition tolerance.

Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated the effect of fenugreek seed powder as an adjunct to other drugs to treat enteral nutrition intolerance in critically ill patients. As a result, the use of fenugreek seeds in the treatment plan of this patient population is recommended.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CCBY4.0) which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

List of abbreviations

DGE: Delayed gastric emptying; EN: Enteral nutrition; GIMM: gastrointestinal microbiome modulator; GRV: Gastric Residual Volume.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board of Sabzevar University approved the protocol of the present study (Code of ethics: IR.MEDSAB.REC.1394.128).

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the research. AK, AZ, MR, HGM and YT collected the Data. AZ and YT conducted analysis and interpretation of data. All authors drafted the first version. AK, AZ, MR and HGM edited the first draft. All authors reviewed, commented and approved the final draft.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences. We cordially thank of all the staff at units ICU (Dr, Shahid Beheshti’s unit and the Mohammad Vasei) for collaborating In treatments of the participants. Special thanks of all the patients, family members that participated in the study.

References

-

Hegazi

Refaat A,

Wischmeyer

Paul E.

Clinical review: optimizing enteral nutrition for critically ill patients-a simple data-driven formula. Critical Care.

2011;

15

(6)

:

234

.

-

Uozumi

M.,

Sanui

M.,

Komuro

T.,

Iizuka

Y.,

Kamio

T.,

Koyama

H..

Interruption of enteral nutrition in the intensive care unit: a single-center survey. Journal of Intensive Care.

2017;

5

:

52

.

-

Montejo

J. C.,

The

Nutritional,

Metabolic Working Group of the Spanish Society of Intensive Care

Medicine,

Coronary

Units.

Enteral nutrition-related gastrointestinal complications in critically ill patients: a multicenter study. Critical Care Medicine.

1999;

27

:

1447-53

.

-

McClave

S. A.,

Taylor

B. E.,

Martindale

R. G.,

Warren

M. M.,

Johnson

D. R.,

Braunschweig

C.,

Society of Critical Care

Medicine,

American Society for

Parenteral,

Enteral

Nutrition.

Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.

2016;

40

:

159-211

.

-

Ritz

Marc A,

Fraser

Robert,

Tam

William,

Dent

John.

Impacts and patterns of disturbed gastrointestinal function in critically ill patients. The American journal of gastroenterology.

2000;

95

(11)

:

3044

.

-

Burton

J. H.,

Johnson

M.,

Johnson

J.,

Hsia

D. S.,

Greenway

F. L.,

Heiman

M. L..

Addition of a gastrointestinal microbiome modulator to metformin improves metformin tolerance and fasting glucose levels. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology.

2015;

9

:

808-14

.

-

Valcheva

R.,

Dieleman

L. A..

Prebiotics: definition and protective mechanisms. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Gastroenterology.

2016;

30

:

27-37

.

-

Hiesmayr

M..

Nutrition risk assessment in the ICU. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care.

2012;

15

:

174-80

.

-

Meyer

D..

Health benefits of prebiotic fibers. Advances in Food and Nutrition Research.

2015;

74

:

47-91

.

-

Macfarlane

S.,

Macfarlane

G. T.,

Cummings

J. H..

Review article: prebiotics in the gastrointestinal tract. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics.

2006;

24

:

701-14

.

-

Codner

P. A..

Enteral nutrition in the critically ill patient. The Surgical Clinics of North America.

2012;

92

:

1485-501

.

-

Khorshidian

Nasim,

Yousefi Asli

Mojtaba,

Arab

Masoumeh,

Adeli Mirzaie

Abolfazl,

Mortazavian

Amir Mohammad.

Fenugreek: potential applications as a functional food and nutraceutical. Nutrition and Food Sciences Research.

2016;

3

(1)

:

5-16

.

-

Chevassus

H.,

Gaillard

J. B.,

Farret

A.,

Costa

F.,

Gabillaud

I.,

Mas

E..

A fenugreek seed extract selectively reduces spontaneous fat intake in overweight subjects. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology.

2010;

66

:

449-55

.

-

Srinivasan

K.

Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum): A review of health beneficial physiological effects. Food reviews international.

2006;

22

(2)

:

203-224

.

-

D

Prajapati Ashish,

V.P

Sancheti,

S.P.M.

Review article on fenugreek plant with it ’ s medicinal uses. nternational Journal of Phytotherapy Research.

2014;

1

(4)

:

39-55

.

-

Laila

Omi,

Murtaza

Imtiyaz,

Abdin

MZ,

Showkat

Sageera.

Germination of fenugreek seeds improves hypoglycaemic effects and normalizes insulin signilling pathway efficiently in diabetes. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research.

2016;

7

(4)

:

1535

.

-

Moradi

N,

Moradi

K.

Physiological and pharmaceutical effects of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) as a multipurpose and valuable medicinal plant. Global journal of medicinal plant research.

2013;

1

(2)

:

199-206

.

-

Avalos-Soriano

Anaguiven,

De la Cruz-Cordero

Ricardo,

Rosado

Jorge L,

Garcia-Gasca

Teresa.

4-Hydroxyisoleucine from Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum): Effects on Insulin Resistance Associated with Obesity. Molecules.

2016;

21

(11)

:

1596

.

-

Rotblatt

M..

Herbal Medicine: Expanded Commission E Monographs. Annals of Internal Medicine.

2000;

133

:

487

.

-

Kaur

M..

IJBCP International Journal of Basic & Clinical Pharmacology Research Article To study the efficacy and tolerability of fenugreek seed powder as add- on therapy with metformin in patients of type-2 diabetes mellitus. International Journal of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology.

2016;

5

:

378-83

.

-

Helmy

H. M..

Study the Effect of Fenugreek Seeds on Gastric Ulcer in Experimental Rats. 2011;

6

:

152-8

.

-

Ramakrishna Rao

R,

Platel

Kalpana,

Srinivasan

K.

In vitro influence of spices and spice-active principles on digestive enzymes of rat pancreas and small intestine. Food/Nahrung.

2003;

47

(6)

:

408-412

.

-

Ghochae

A..

The survey of the effect of ginger extract on gastric residual volume in mechanically ventilated patients hospitalized in the Intensive Care Units. Advances in Environmental Biology.

2013;

7

:

3395-400

.

-

Wani

Sajad Ahmad,

Kumar

Pradyuman.

Fenugreek: A review on its nutraceutical properties and utilization in various food products. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences.

2018;

17

(2)

:

97-106

.

-

Lilly

C. M.,

Cody

S.,

Zhao

H.,

Landry

K.,

Baker

S. P.,

McIlwaine

J.,

University of Massachusetts Memorial Critical Care Operations

Group.

Hospital mortality, length of stay, and preventable complications among critically ill patients before and after tele-ICU reengineering of critical care processes. Journal of the American Medical Association.

2011;

305

:

2175-83

.

-

Meghwal

M. G..

A Review on the Functional Properties, Nutritional Content, Medicinal Utilization and Potential Application of Fenugreek. Journal of Food Processing & Technology.

2012;

3

.

-

Kannappan

S,

Anuradha

CV,

others

Insulin sensitizing actions of fenugreek seed polyphenols, quercetin & metformin in a rat model. Indian journal of medical research.

2009;

129

(4)

:

401

.

-

Ulbricht

Catherine,

Basch

Ethan,

Burke

Dilys,

Cheung

Lisa,

Ernst

Edzard,

Giese

Nicole,

Foppa

Ivo,

Hammerness

Paul,

Hashmi

Sadaf,

Kuo

Grace,

others

Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L. Leguminosae): an evidence-based systematic review by the natural standard research collaboration. Journal of herbal pharmacotherapy.

2008;

7

(3-4)

:

143-177

.

-

Chevassus

H.,

Molinier

N.,

Costa

F.,

Galtier

F.,

Renard

E.,

Petit

P..

A fenugreek seed extract selectively reduces spontaneous fat consumption in healthy volunteers. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology.

2009;

65

:

1175-8

.

-

El Nasri

Nazar A,

El Tinay

AH.

Functional properties of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum graecum) protein concentrate. Food chemistry.

2007;

103

(2)

:

582-589

.

-

Hamza

Reham Zakaria Mustafa Mohammed.

Anti-ulcer and gastro protective effects of fenugreek, ginger and peppermint oils in experimentally induced gastric ulcer in rats. Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research (ISSN: 0975-7384).

2014;

:

451-468

.

-

Vazquez-Sandoval

Ghamande

Alfredo and,

Surani

Shekhar and,

Salim

Critically ill patients and gut motility: Are we addressing it?. World journal of gastrointestinal pharmacology and therapeutics.

2017;

8

(3)

:

174-179

.

-

Bernard

A. C..

Nutrition in Clinical Practice Defining and Assessing Tolerance in Enteral Nutrition Clinical Dilemma Defining and Assessing Tolerance in Enteral Nutrition. Nutrition in Clinical Practice.

2004;

19

.

-

Heyland

D. K.,

Cahill

N. E.,

Dhaliwal

R.,

Sun

X.,

Day

A. G.,

McClave

S. A..

Impact of enteral feeding protocols on enteral nutrition delivery: results of a multicenter observational study. JPEN. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.

2010;

34

:

675-84

.

-

Montejo González

J. C.,

Estébanez Montiel

B..

[Gastrointestinal complications in critically ill patients]. Nutrición Hospitalaria.

2007;

22

:

56-62

.

Comments

Downloads

Article Details

Volume & Issue : Vol 5 No 7 (2018)

Page No.: 2528-2537

Published on: 2018-07-28

Citations

Copyrights & License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Search Panel

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Search for this article in:

Google Scholar

Researchgate

- HTML viewed - 6416 times

- Download PDF downloaded - 1891 times

- View Article downloaded - 0 times

Biomedpress

Biomedpress