Abstract

Background: Plaque psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease. Conventional treatments of psoriasis are not completely effective. In addition, unwanted side effects limit their long-term use. In this regard, developing new natural treatments with fewer side effects could be an alternative option. This study was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of topical chamomile-pumpkin oleogel (ChP) in treating plaque psoriasis.

Methods: A total of 40 patients with mild-to-moderate plaque psoriasis were enrolled in this intra-patient, double-blind, block-randomized clinical trial. In each patient, bilateral symmetrical plaques were treated with ChP or placebo twice daily for four weeks. For clinical assessment, the Psoriasis Severity Index (PSI) and the Physician's Global Assessment (PGA) scale were evaluated at baseline and after the treatment. At the end of the study, patients' satisfaction with the treatment was evaluated using a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 0 to 10. For safety assessment, all treatment-related side effects were recorded.

Results: Thirty-seven subjects (20 female, 17 male; age 20–60 years) completed the study. The mean decreases in the PSI score in the ChP group (4.09 +/- 2.24) were significantly (p = 0.000) greater than the placebo group (0.48 +/- 1.39). According to the PGA results, 13/37 (35%) of the ChP-treated plaques could achieve marked to complete improvement compared to 0% in the placebo group. Three patients dropped out from the study due to worsening of bilateral plaques during the first week of trial.

Conclusion: Our results suggest that topically applied ChP could provide a safe and effective complementary option for psoriasis plaque management. IRCT registration code: IRCT2016092830030N1.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic and complex autoimmune skin disease with a prevalence of 2–4% in the world 1. The most prevalent (up to 90%) sub-type of this disease is plaque psoriasis, which is characterized by raised erythematous scaly skin patches 2. The infiltration of dysregulated immunocytes in the skin layers and subsequent inflammation is responsible for the development of clinical plaques 3. These plaques tend to be symmetrically distributed on extensor areas of scalp, elbows, trunk, and knees 4.

Although this disease is not life-threatening, it has major negative impacts on the patient's psychosocial health 5. Psychological distress and disability in this condition are not necessarily related to disease severity, and even mild psoriasis can have a great impact on the well-being of patients 6.

In conventional medicine, topical or systemic medications and phototherapy are administered based on the severity of psoriasis. Topical therapy is the mainstay of mild psoriasis management and adjunct to systemic treatments in severe cases 7. The most frequently anti-psoriasis topical drugs are corticosteroids, vitamin A derivatives, vitamin D analogues, calcineurin inhibitors, and coal tar. Unfortunately, most of these drugs cause unwanted side effects such as skin irritation, infections, malignancy, atrophy, purpura, telangiectasia, photosensitivity, and rebound symptoms 8. Given that psoriasis is lifelong relapsing and difficult-to-treat-disorder, developing new alternative treatments with fewer side effects and higher efficacy is necessary 9. In this regard, the use of traditional, complementary, and alternative (TM/CAM) modalities is promising. Recent studies have shown that the demand for such treatments among psoriasis patients has increased in the last decades 10.

Iranian Traditional medicine (ITM) is one of the most ancient traditional systems of medicine with a history of thousands of years 11. In ITM, plaque psoriasis is classified as a subtype of a disease named Ghouba 12. In ITM textbooks, herbal oils such as pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L.) seed oil and chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) oil (aqueous chamomile extract in sesame oil vehicle) are recommended for topical management of psoriasis 13.

The therapeutic effects of topical chamomile on inflammatory skin conditions such as atopic eczema 14, diaper rash 1516 radiation dermatitis 17 and phlebitis 18 have been documented in several studies. However, studies on the topical dosage forms of pumpkin seeds are limited. In an animal model of chronic skin inflammation, topical pumpkin seed oil could reduce edema, congestion, cells infiltration, and keratinocyte hyperproliferation as well as dexamethasone 19.

To date, no study has investigated the therapeutic effect of topical preparations of chamomile or pumpkin seed oil on psoriasis. However, the documented anti-inflammatory effects of chamomile 20 and pumpkin seed oil 19 provide hypothetical support for their probable therapeutic effect on plaque psoriasis. This study was designed to evaluate the efficacy of a semi-solid topical herbal preparation made from the aforementioned herbal oils (ChP) on plaque psoriasis.

Methods

Study design

This randomized intra-patient double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial was conducted at the Department of Dermatology at the Razi Hospital of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, between September 2017 and March 2018.

Ethical issues

This clinical trial was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (approval code: IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1395.184). This study was registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials website (IRCT2016092830030N1). After explaining the purpose of the trial to the patient, written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Preparation of ChP oleogel and placebo

The ChP oleogel was a mixture of traditional M. chamomilla oil (direct heat method), C. pepo seed oil, and colloidal silicon dioxide (47.5%: 47.5%: 5%). The placebo oleogel consisted of traditional M. chamomilla oil, C. pepo seed oil, silicon dioxide, and liquid paraffin (0.5%: 0.5%: 5%: 94%). The texture, color, and smell of these two formulations were similar.

Traditional chamomile oil was prepared based on the direct heat method, which was standardized in previous studies 2122. In this method, chamomile flower was powdered and boiled in water to achieve an aqueous extract. Then, after filtering the mixture, the aqueous extract was mixed with sesame oil and then boiled to evaporate all water content. The remaining oil is called chamomile oil. Also, standard pumpkin seed oil was purchased from the Giah Essence Phytopharm Co., Iran.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We enrolled 40 patients of both sexes using the eligibility criteria listed in the Table 1.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis of mild to moderate plaque-type psoriasis by a dermatologist | Pregnancy or lactation |

| The presence of at least two symmetric psoriasis plaques | Systemic therapy or phototherapy within the last four months before study |

| Age between 20 and 60 years | Need to start systemic therapy during the study |

| Discontinuation of topical treatment for at least two weeks prior to the study | Use of medications that could induce or exacerbate psoriasis during the study |

| Patient consent to participate in the study | Skin infection or malignancy in the treatment area |

| History of allergic reaction to the herbal ingredients of the drug | |

| The unwillingness of patients to continue treatment |

Randomization and blinding

To ensure balance in the treatment side (left or right), block randomization with a 1:1 ratio and block size of four participants was performed. The principal investigator prepared sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes for allocation of treatment. The investigators and patients remained unaware of treatment allocation. The codes of ChP and placebo were only revealed after the trial was completed.

Intervention

The patients first signed the written informed consent. Then symmetrical target lesions in each patient were selected to receive ChP or placebo, twice daily for four weeks.

Outcome assessment

A dermatologist who was blind to randomization scored the severity of erythema, scaling, and induration of plaques with an 8-point scale (0 = none, 2 = mild, 4 = moderate, 6 = severe, 8 = very severe). The response to the treatment was evaluated based on the mean reduction in the erythema, scaling, induration, and PSI scores from baseline. The PSI score is the sum of erythema, scaling, and induration score, and ranges from 0 to 24.

In addition, we used the Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) scale as follows: worse, no change (0%), mild improvement (0–25%), moderate improvement [25–50%), marked improvement [50–75%), almost clear [75–100%), and completely clear (100%). Photographs of the lesions were taken at baseline and the fourth week.

Patient satisfaction with the ChP and placebo was evaluated using a visual analog scale of 0 (completely dissatisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied). Additionally, the patients were asked to report all treatment-related side effects during the study.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of 40 was estimated by considering the significance level of 5%, the power of 80%, and a probable 20% drop-out rate. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16. All patients who completed the study were included in the statistical analysis. A Wilcoxon’s matched-pairs signed-ranks test was conducted to establish the difference between the baseline and post-treatment values and the difference between the changes in the ChP and placebo sides. All the statistical tests were two-sided with the significance level of 0.05.

Results

Of the 40 patients enrolled in our study, 37 (20 female and 17 male) completed it. Three patients withdrew from the trial due to local side effects after application of the medications. The recruitment of the patients is shown in the CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 1).

The average age of the patients was 36.8 ± 13.3 years (range, 20–60 years). The mean duration of the psoriasis disease was 12.11 ± 6.2 years (range, 2–31 years) and the mean Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score was 6.58 ± 3.22 (range 1.2–10.1).

Forty symmetrical target lesions were selected, in which 16 pairs were located on upper extremities and 24 pairs were located on lower extremities.

Four weeks after treatment, the average PSI score decline in the ChP group (4.09 ± 2.24) was significantly (p = 0.000) greater than the placebo group (0.48 ± 1.39). The mean values of the erythema, scaling, induration, and PSI scores at baseline and four weeks after treatment are summarized in Table 2.

| Item | Group | Baseline (n=37) mean± SD | 4th week (n=37) mean± SD | Pa |

| Erythema score | ChP | 3.44 ± 1.36 | 2.44 ± 1.21 | 0.000 |

| placebo | 3.34 ± 1.25 | 3.21 ± 1.22 | 0.052 | |

| Scaling score | ChP | 4.09 ± 1.38 | 2.28 ± 1.55 | 0.000 |

| placebo | 3.80 ± 1.30 | 3.63 ± 1.34 | 0.170 | |

| Induration score | ChP | 3.46 ± 0.93 | 2.17 ± 0.96 | 0.000 |

| placebo | 3.27 ± 0.95 | 3.09 ± 0.99 | 0.039 | |

| PSI score | ChP | 11 ± 2.64 | 6.90 ± 3.04 | 0.000 |

| placebo | 10.42 ± 2.71 | 9.94 ± 2.56 | 0.019 |

The mean ± SD decrease in the erythema, scaling, and induration scores were 1 ± 1, 1.80 ± 1.1, and 1.28 ± 1.03 in the ChP group, respectively, and 0.13 ± 0.48, 0.17 ± 0.87, and 0.17 ± 0.58 in the placebo group, respectively. In between group comparisons, these changes were significantly (p < 0.05) in favor of ChP treatment.

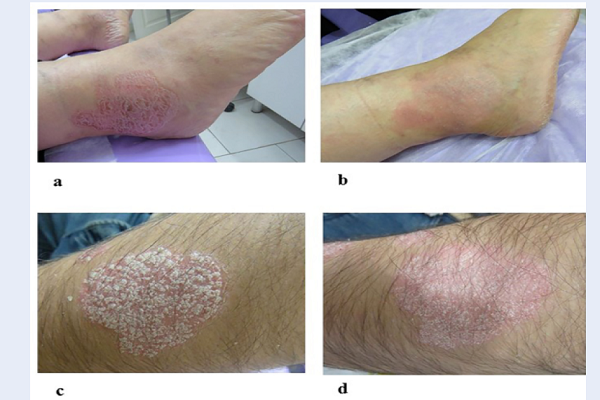

Regarding the Physician’s Global Assessment, 50% or greater improvement at week four was seen in 35% (13/37) of the ChP treated plaques versus 0% of the placebo-treated plaques. Of the 40 plaques treated with ChP, 54% showed moderate to marked improvement, and 14% became almost or completely clear. In the placebo group, 41% and 16% of the plaques found respectively mild and moderate improvement (Figure 2). The clinical effectiveness of the ChP is shown in figure 3 (Figure 3).

The overall patient satisfaction score on a 0–10 VAS was 4.77 ± 2.22 in the ChP group and 1.92 ± 1.13 in the placebo group.

Safety was assessed by recording adverse drug reactions and patient withdrawal from the study. During the first week of treatment, three of the forty subjects enrolled experienced itching and irritation of contralateral plaques which was more severe in the ChP treated side. These symptoms resolved 24 hours after discontinuation of the treatments, but these patients were excluded due to an unwillingness to continue the trial. In the remaining 37 patients, the ChP was well tolerated without any side effect.

Discussion

Topical therapy is an important part of psoriasis management especially in mild to moderate cases. Unfortunately, conventional topical drugs have side effects, which limit their long-term use 23. Developing new anti-psoriasis drugs from medicinal plants could be a promising option. In this regard, we assessed the clinical efficacy of a topical preparation (ChP) containing chamomilla oil and pumpkin seed oil on mild to moderate plaque psoriasis. Because psoriasis is a multifactorial disease, we chose an intra-patient method to decrease the possible effect of variables such as sex, age, BMI, lifestyle habits, etc. on therapeutic response. This pilot study revealed that four weeks of treatment with ChP significantly improved erythema, scaling, thickness, and PSI scores compared with the placebo.

Psoriasis is an immune -mediated inflammatory skin disease with a complex pathogenesis that is not completely understood. Complex interactions among keratinocytes, activated T cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells are involved in the development of this disease 24. Reactions of these immune cells in skin layers induce inflammatory mediators release, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and cellular damage. All of these inflammatory reactions lead to keratinocyte hyperproliferation and psoriatic lesion formation 25.

The effect of externally applied chamomilla preparations was investigated in several inflammatory skin conditions. In a study on patients with inflammatory dermatoses, the clinical efficacy of Kamillosan cream (containing German chamomilla extract) was equivalent to hydrocortisone and superior to diflucortolone and bufexamac 26. In another study on peristomal skin lesions, the mean time for healing with a topical chamomilla solution was significantly greater than hydrocortisone 27. These therapeutic effects of chamomilla could be attributed to biological ingredients including flavonoids (apigenin, luteolin, and quercetin) and terpenoids (α-bisabolol, chamazulene). These compounds exert anti-inflammatory effects through different mechanisms including anti-oxidant activities 2829303132, and inhibitory effects on the production of inflammatory mediators such as LTB4, PGE2, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and nitric oxide 3334353637. Also, sesame oil (used as a vehicle for chamomilla oil preparation) has compounds with anti-proliferative 38, anti-inflammatory 3940 and anti-oxidant properties 41. Additionally, both sesame oil 42 and pumpkin seed oil 43 are rich in linoleic acid (LA) which is an essential fatty acid in the stratum corneum (SC) barrier structure. Recent studies revealed the relationship between skin barrier disruption and psoriasis pathogenesis 44. Any defect in the SC barrier could result in keratinocyte hyper-proliferation and cytokine release 45. The SC consists of corneocytes embedded in an intercellular matrix. The presence of a lipid matrix rich in ceramides, cholesterol, and fatty acids is necessary for maintaining skin barrier function 46. LA is the predominant fatty acid in the SC and is the main precursor of ceramides 47. LA has a major role in preserving skin barrier integrity, and one of its metabolites named 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid has antiproliferative properties 48.

In addition to LA, pumpkin seed oil has a high content of tocopherols, Selenium, β carotene, and phenolic compounds, all of which provide antioxidant effects 49.

In most of the patients, ChP was well tolerated, and no serious adverse event was reported. Three patients experienced bilateral irritation of plaque psoriasis and dropped out from the study. These side effects could be due to an allergic reaction to one of the herbal ingredients of the ChP and placebo. Chamomile is listed as GRAS (generally recognized as safe) by the FDA and has been used as a topical treatment in different dermatologic conditions for centuries 50. Sesame seed oil is widely used in cosmetic products and the Cosmetic Ingredient Review (CIR) Expert Panel has confirmed its safety 51. Although not common, allergic reactions after the topical use of Chamomile525354555657 and sesame oil 585960 were documented in several case reports. Therefore, this formulation should be used with caution in patients with a history of allergic reaction to these herbs.

We acknowledge some limitations of our study including lack of comparison with a conventional topical anti-psoriasis drug (e.g. corticosteroid) and short-term follow-up period.

Conclusion

This is the first study to evaluate the efficacy of a herbal formulation containing chamomile and pumpkin seed oil in the treatment of plaque psoriasis. Our findings suggest that ChP could be a safe and effective therapeutic option in mild to moderate plaque psoriasis. This therapeutic response could be related to the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of the ChP ingredients. Further clinical trials with larger sample size and longer observation are needed to confirm our results and to compare the effectiveness of ChP with conventional anti-psoriasis drugs.

Competing Interests

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Sima Kolahdooz: study design, data acquisition, data analysis, and manuscript preparation

Mehrdad Karimi: Study design, manuscript preparation

Nafiseh Esmaili: patient recruitment and selection

Arman Zargaran: drug formulation, review and revise the manuscript

Gholamreza Kordafshari: patient recruitment

Nikoo Mozafari: patient recruitment and selection and data interpretation

Mohammad. Hossein Ayati: data analysis

All authors read the final version of article and approved it.

Abbreviations

ChP: Chamomile-pumpkin oleogel

CIR: Cosmetic Ingredient Review

GRAS: Generally recognized as safe

ITM: Iranian Traditional medicine

LA: Linoleic acid

PASI: Psoriasis Area and Severity Index

PGA: Physician’s Global Assessment

PSI: Psoriasis Severity Index

ROS: Reactive oxygen species

SC: Stratum corneum

TM/CAM: Traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine

VAS: Visual analog scale

References

-

Lima

X. T.,

Minnillo

R.,

Spencer

J. M.,

Kimball

A. B..

Psoriasis prevalence among the 2009 AAD National Melanoma/Skin Cancer Screening Program participants. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

2013;

27

:

680-5

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Luba

K. M.,

Stulberg

D. L..

Chronic plaque psoriasis. South African Family Practice.

2006;

73

:

636-44

.

-

Krueger

J. G.,

Bowcock

A..

Psoriasis pathophysiology: current concepts of pathogenesis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

2005;

64

:

ii30-6

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Johnson

M. A.,

Armstrong

A. W..

Clinical and histologic diagnostic guidelines for psoriasis: a critical review. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology.

2013;

44

:

166-72

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kimball

A. B.,

Jacobson

C.,

Weiss

S.,

Vreeland

M. G.,

Wu

Y..

The psychosocial burden of psoriasis. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology.

2005;

6

:

383-92

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Stern

R. S.,

Nijsten

T.,

Feldman

S. R.,

Margolis

D. J.,

Rolstad

T..

Psoriasis is common, carries a substantial burden even when not extensive, and is associated with widespread treatment dissatisfaction. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. Symposium Proceedings.

2004;

9

:

136-9

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Bos

J. D.,

Spuls

P. I..

Topical treatments in psoriasis: today and tomorrow. Clinics in Dermatology.

2008;

26

:

432-7

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kamel

J. G.,

Yamauchi

P. S..

Managing Mild-to-Moderate Psoriasis in Elderly Patients: Role of Topical Treatments. Drugs & Aging.

2017;

34

:

583-8

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Herman

A.,

Herman

A. P..

Topically Used Herbal Products for the Treatment of Psoriasis - Mechanism of Action, Drug Delivery, Clinical Studies. Planta Medica.

2016;

82

:

1447-55

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Smith

N.,

Weymann

A.,

Tausk

F. A.,

Gelfand

J. M..

Complementary and alternative medicine for psoriasis: a qualitative review of the clinical trial literature. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

2009;

61

:

841-56

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Rezaeizadeh

H.,

Alizadeh

M.,

Naseri

M.,

Ardakani

M..

The Traditional Iranian Medicine Point of View on Health and disease. Iranian Journal of Public Health.

2009;

38

:

169-72

.

-

Atyabi

A.,

Shirbeigi

L.,

Eghbalian

F..

Psoriasis and topical Iranian traditional medicine. Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences.

2016;

41

:

S54

.

-

Aghili

Khorasani,

MH

Shirazi.

Qarabadin-e-Kabir 1970.

Google Scholar -

Patzelt-Wenczler

R.,

Ponce-Poschl

E..

Proof of efficacy of Kamillosan(R) cream in atopic eczema. European Journal of Medical Research.

2000;

5

:

171-5

.

-

Badelbuu

Sima Ghanipour,

Javadzadeh

Yousef,

Jabraeili

Mahnaz,

Heidari

Shiva,

Bostanabad

Mohammad Arshadi.

Evaluation of the Effect of Aloe Vera Ointment with Chamomile Ointment on Severity of Children’s Diaper Dermatitis: A randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Middle East Journal of Family Medicine.

2018;

7

:

47

.

-

Afshari

Zahra,

Jabraeili

Mahnaz,

Asaddollahi

Maliheh,

Ghojazadeh

Morteza,

Javadzadeh

Yusuf.

Comparison of the effects of chamomile and calendula ointments on diaper rash. Evidence Based Care.

2015;

5

:

49-56

.

-

Maiche

A. G.,

Grohn

P.,

Maki-Hokkonen

H..

Effect of chamomile cream and almond ointment on acute radiation skin reaction. Acta Oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden).

1991;

30

:

395-6

.

-

Reis

Paula Elaine Diniz dos,

Carvalho

Emilia Campos de,

Bueno

Paula Carolina Pires,

Bastos

Jairo Kenupp.

Clinical application of Chamomilla recutita in phlebitis: dose response curve study. Revista latino-americana de enfermagem.

2011;

19

:

03-10

.

-

de Oliveira

M. L.,

Nunes-Pinheiro

D. C.,

Bezerra

B. M.,

Leite

L. O.,

Tome

A. R.,

Girao

V. C..

Topical Anti-inflammatory Potential of Pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L.) Seed Oil on Acute and Chronic Skin Inflammation in Mice. Acta Scientiae Veterinariae.

2013;

41

:

1-9

.

-

Miraj

S.,

Alesaeidi

S..

A systematic review study of therapeutic effects of Matricaria recuitta chamomile (chamomile). Electronic Physician.

2016;

8

:

3024-31

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Zargaran

A.,

Borhani-Haghighi

A.,

Salehi-Marzijarani

M.,

Faridi

P.,

Daneshamouz

S.,

Azadi

A..

Evaluation of the effect of topical chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) oleogel as pain relief in migraine without aura: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Neurological Sciences.

2018;

39

:

1345-53

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Zargaran

A.,

Sakhteman

A.,

Faridi

P.,

Daneshamouz

S.,

Akbarizadeh

A. R.,

Borhani-Haghighi

A..

Reformulation of Traditional Chamomile Oil: Quality Controls and Fingerprint Presentation Based on Cluster Analysis of Attenuated Total Reflectance-Infrared Spectral Data. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine.

2017;

22

:

707-14

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Feldman

S. R.,

Horn

E. J.,

Balkrishnan

R.,

Basra

M. K.,

Finlay

A. Y.,

McCoy

D.,

International Psoriasis

Council.

Psoriasis: improving adherence to topical therapy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

2008;

59

:

1009-16

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Cai

Y.,

Fleming

C.,

Yan

J..

New insights of T cells in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Cellular & Molecular Immunology.

2012;

9

:

302-9

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Zhou

Q.,

Mrowietz

U.,

Rostami-Yazdi

M..

Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Free Radical Biology & Medicine.

2009;

47

:

891-905

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Aertgeerts

P.,

Albring

M.,

Klaschka

F.,

Nasemann

T.,

Patzelt-Wenczler

R.,

Rauhut

K..

[Comparative testing of Kamillosan cream and steroidal (0.25% hydrocortisone, 0.75% fluocortin butyl ester) and non-steroidal (5% bufexamac) dermatologic agents in maintenance therapy of eczematous diseases]. Zeitschrift fur Hautkrankheiten.

1985;

60

:

270-7

.

-

Charousaei

F.,

Dabirian

A.,

Mojab

F..

Using chamomile solution or a 1% topical hydrocortisone ointment in the management of peristomal skin lesions in colostomy patients: results of a controlled clinical study. Ostomy/Wound Management.

2011;

57

:

28-36

.

-

Stanojevic

Ljiljana P,

Marjanovic-Balaban

Zeljka R,

Kalaba

Vesna D,

Stanojevic

Jelena S,

Cvetkovic

Dragan J.

Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of chamomile flowers essential oil (Matricaria chamomilla L.). Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants.

2016;

19

:

2017-2028

.

-

Roby

M. H.,

Sarhan

M. A.,

Selim

K. A.,

Khalel

K. I..

Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of essential oil and extracts of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare L.) and chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.). Industrial Crops and Products.

2013;

44

:

437-45

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Owlia

P.,

Rasooli

I.,

Saderi

H..

Antistreptococcal and antioxidant activity of essential oil from Matricaria chamomilla L. Research Journal of Biological Sciences.

2007;

2

:

237-9

.

-

Osman

Mona Y,

Taie

Hanan AA,

Helmy

Wafaa A,

Amer

Hassan.

Screening for antioxidant, antifungal, and antitumor activities of aqueous extracts of chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla). Egyptian Pharmaceutical Journal.

2016;

15

:

55

.

-

Kolodziejczyk-Czepas

J.,

Bijak

M.,

Saluk

J.,

Ponczek

M. B.,

Zbikowska

H. M.,

Nowak

P..

Radical scavenging and antioxidant effects of Matricaria chamomilla polyphenolic-polysaccharide conjugates. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules.

2015;

72

:

1152-8

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Bhaskaran

N.,

Shukla

S.,

Srivastava

J. K.,

Gupta

S..

Chamomile: an anti-inflammatory agent inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by blocking RelA/p65 activity. International Journal of Molecular Medicine.

2010;

26

:

935-40

.

-

Safayhi

H.,

Sabieraj

J.,

Sailer

E. R.,

Ammon

H. P..

Chamazulene: an antioxidant-type inhibitor of leukotriene B4 formation. Planta Medica.

1994;

60

:

410-3

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Srivastava

J. K.,

Pandey

M.,

Gupta

S..

Chamomile, a novel and selective COX-2 inhibitor with anti-inflammatory activity. Life Sciences.

2009;

85

:

663-9

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Curra

M.,

Martins

M. A.,

Lauxen

I. S.,

Pellicioli

A. C.,

Sant\'Ana Filho

M.,

Pavesi

V. C..

Effect of topical chamomile on immunohistochemical levels of IL-1? and TNF-? in 5-fluorouracil-induced oral mucositis in hamsters. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology.

2013;

71

:

293-9

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Maurya

A. K.,

Singh

M.,

Dubey

V.,

Srivastava

S.,

Luqman

S.,

Bawankule

D. U..

?-(-)-bisabolol reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine production and ameliorates skin inflammation. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology.

2014;

15

:

173-81

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Zhou

Lin,

Lin

Xiaohui,

Abbasi

Arshad Mehmood,

Zheng

Bisheng.

Phytochemical contents and antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of selected black and white sesame seeds. BioMed research international.

2016;

2016

.

-

Monteiro

E. M.,

Chibli

L. A.,

Yamamoto

C. H.,

Pereira

M. C.,

Vilela

F. M.,

Rodarte

M. P..

Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of the sesame oil and sesamin. Nutrients.

2014;

6

:

1931-44

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Hsu

Dur-Zong,

Chu

Pei-Yi,

Liu

Ming-Yie.

Sesame seed (Sesamum indicum L.) extracts and their anti-inflammatory effect. Emerging Trends in Dietary Components for Preventing and Combating Disease.

2012;

1093

:

335-341

.

-

Carvalho

R.,

Galvao

E.,

Barros

J.,

Conceicao

M.,

Sousa

E..

Extraction, fatty acid profile and antioxidant activity of sesame extract (Sesamum Indicum L.). Brazilian Journal of Chemical Engineering.

2012;

29

:

409-20

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Yol

E.,

Toker

R.,

Golukcu

M.,

Uzun

B..

Oil Content and Fatty Acid Characteristics in Mediterranean Sesame Core Collection. Crop Science.

2015;

55

:

2177

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Gohari Ardabili

A.,

Farhoosh

R.,

Haddad Khodaparast

M. H..

Chemical composition and physicochemical properties of pumpkin seeds (Cucurbita pepo subsp. pepo var. Styriaka) grown in Iran. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology.

2011;

13

:

1053-63

.

-

Sano

S..

Psoriasis as a barrier disease. Zhonghua Pifuke Yixue Zazhi.

2015;

33

:

64-9

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Ye

L.,

Lv

C.,

Man

G.,

Song

S.,

Elias

P. M.,

Man

M. Q..

Abnormal epidermal barrier recovery in uninvolved skin supports the notion of an epidermal pathogenesis of psoriasis. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

2014;

134

:

2843-6

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Menon

G. K.,

Cleary

G. W.,

Lane

M. E..

The structure and function of the stratum corneum. International Journal of Pharmaceutics.

2012;

435

:

3-9

.

View Article Google Scholar -

McCusker

M. M.,

Grant-Kels

J. M..

Healing fats of the skin: the structural and immunologic roles of the ?-6 and ?-3 fatty acids. Clinics in Dermatology.

2010;

28

:

440-51

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Ziboh

V. A.,

Miller

C. C.,

Cho

Y..

Metabolism of polyunsaturated fatty acids by skin epidermal enzymes: generation of antiinflammatory and antiproliferative metabolites. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

2000;

71

:

361S-6S

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Eraslan

G.,

Kanbur

M.,

Aslan

O.,

Karabacak

M..

The antioxidant effects of pumpkin seed oil on subacute aflatoxin poisoning in mice. Environmental Toxicology.

2013;

28

:

681-8

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Srivastava

J. K.,

Shankar

E.,

Gupta

S..

Chamomile: A herbal medicine of the past with bright future. Molecular Medicine Reports.

2010;

3

:

895-901

.

-

Johnson

Wilbur,

Bergfeld

Wilma F,

Belsito

Donald V,

Hill

Ronald A,

Klaassen

Curtis D,

Liebler

Daniel C,

Marks

James G,

Shank

Ronald C,

Slaga

Thomas J,

Snyder

Paul W.

Amended safety assessment of sesamum indicum (sesame) seed oil, hydrogenated sesame seed oil, sesamum indicum (sesame) oil unsaponifiables, and sodium sesameseedate. International journal of toxicology.

2011;

30

:

40S-53S

.

-

Foti

C.,

Nettis

E.,

Panebianco

R.,

Cassano

N.,

Diaferio

A.,

Pia

D. P..

Contact urticaria from Matricaria chamomilla. Contact Dermatitis.

2000;

42

:

360-1

.

-

McGeorge

B. C.,

Steele

M. C..

Allergic contact dermatitis of the nipple from Roman chamomile ointment. Contact Dermatitis.

1991;

24

:

139-40

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Ozden

M. G.,

Denizli

H.,

Aydin

F.,

Senturk

N.,

Canturk

T.,

Turanli

A. Y..

Allergic concact dermatitis from chamomile plant. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Medicine.

2011;

28

:

29-30

.

View Article Google Scholar -

van Ketel

W. G..

Allergy to Matricaria chamomilla. Contact Dermatitis.

1982;

8

:

143

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Rudzki

E.,

Rapiejko

P.,

Rebandel

P..

Occupational contact dermatitis, with asthma and rhinitis, from camomile in a cosmetician also with contact urticaria from both camomile and lime flowers. Contact Dermatitis.

2003;

49

:

162

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Pereira

F.,

Santos

R.,

Pereira

A..

Contact dermatitis from chamomile tea. Contact Dermatitis.

1997;

36

:

307

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Oiso

N.,

Yamadori

Y.,

Higashimori

N.,

Kawara

S.,

Kawada

A..

Allergic contact dermatitis caused by sesame oil in a topical Chinese medicine, shi-un-ko. Contact Dermatitis.

2008;

58

:

109

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Kubo

Y.,

Nonaka

S.,

Yoshida

H..

Contact sensitivity to unsaponifiable substances in sesame oil. Contact Dermatitis.

1986;

15

:

215-7

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Pecquet

C.,

Leynadier

F.,

Saiag

P..

Immediate hypersensitivity to sesame in foods and cosmetics. Contact Dermatitis.

1998;

39

:

313

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar

Comments

Downloads

Article Details

Volume & Issue : Vol 5 No 11 (2018)

Page No.: 2811-2819

Published on: 2018-11-19

Citations

Copyrights & License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Search Panel

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Search for this article in:

Google Scholar

Researchgate

- HTML viewed - 7612 times

- Download PDF downloaded - 1655 times

- View Article downloaded - 0 times

Biomedpress

Biomedpress