Abstract

Leukemia cutis (LC) is a rare disorder that is distinguished by the infiltration of leukemic cells into the skin. This can be a manifestation of relapse of the previously treated leukemia. We report a case of a 70-year-old woman with acute monocytic leukemia (AMOL), whose disease relapsed and developed into LC after a successful induction therapy. Salvage chemotherapy has been applied successfully to prevent the development of LC in the patient's skin.

Introduction

Leukemia cutis (LC) is known as a general term for skin lesions caused by leukemia 1. In general, this disorder has an incidence of 2.9% -3.7% in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) 2,3. Therefore, AML is the second most common leukemia associated with leukemia cutis 4. Due to a wide range of skin lesions in leukemia cutis, its diagnosis is undistinguishable from other skin disorders. In these cases, immunohistochemistry (IHC) stains can be helpful in the diagnosis of this disease 5. Since leukemia cutis may be a sign of a systemic disorder that occurs before, after, or concurrently with the beginning of AML, treatments should focus on the eradication of systemic leukemia 6. This paper reports a case of leukemia cutis, which occurred after the diagnosis of AML.

Case Presentation

In February 2018, a 70-year-old woman was referred to the Clinic of Hematology and Oncology of Kermanshah with pain, fatigue, night sweats and loss of appetite. The laboratory tests showed a marked leukopenia (1.8 x 109/L), anemia (10.1 g/dL) and thrombocytopenia (145 x 109/L), and a blood film showed 15% of circulating blast cells (Figure 1).

The examination of the bone marrow aspiration (BMA) and bone marrow biopsy (BMB) revealed a hypocellular bone marrow along with a high percentage of blast cells (>30% of monoblast cells). These cells were positive for CD33, CD45, CD68, and lysosomes. According to FAB (French-American-British) classifications, these results were compatible with AML-M5 and treatment was started immediately with azacytidine-based regimens such as CAG (cytarabine, aclarubicin, and G-CSF). After three cycles, the full blood count (FBC) was as follows:

WBC: 3 x 109/L, Hb: 11 g/dL and Plt: 275 x 109/L.

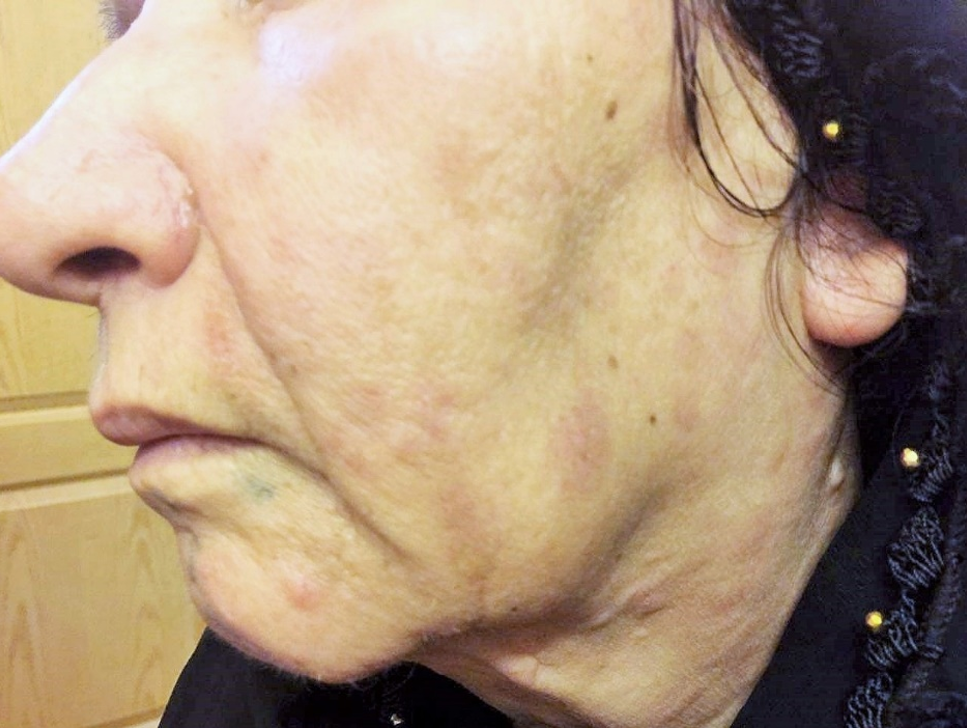

The results demonstrated a relatively good response to treatment. Four months following the initiation of chemotherapy, the patient referred to the dermatologists with a 2-week history of multiple skin lesions such as erythematous and papulonodular rashes on face and neck (Figure 2).

Physical and laboratory examinations revealed gum hypertrophy along with severe leukopenia and raised lactate dehydrogenase levels. Hence, the skin biopsy was performed from suspicious skin lesions on the face, which showed an extensive leukemic cell infiltration into the dermis and the subcutaneous tissues. The results indicated the clear signs of relapsed acute monocytic leukemia LC. The patient was treated with a course of FLAG chemotherapy (fludarabine 30 mg/m2, Ara-C 1 g/m2 for five days, and granulocyte-colony stimulating factors from day six until neutrophil recovery). The patient’s leukemia cutis lesions were resolved within two weeks after the initiation of FLAG chemotherapy, and the patient is a now under follow-up (Figure 3).

Discussion

One of the well-known manifestations of extramedullary AML is leukemia cutis that occurs due to the infiltration of malignant neoplastic leukocytes originated from the bone marrow into different skin layers such as dermis, epidermis, and subcutis 7. In patients with LC, clinical symptoms are variable which include macules, papules, neoformation with the nodular aspect, ulcers and plaques 8,9,10. According to the literature, the most common lesions are macula and neoformation with nodular character 10. The differential diagnosis of LC to other cutaneous lymphomas (i.e., mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome) is based on symptoms such as erythematous or violaceous plaques, papules or nodules, which occur most frequently on face, chest or limbs, whereas, the typical clinical manifestations of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome are respectively hypopigmented lesions and erythroderma 11.

LC is more common in AML- than CML patients. Its prevalence in these patients is around 10 -15% 12. Chromosomal abnormalities (especially trisomy chromosome 8) are also associated with the progression of LC in patients with AML 2. Due to the lack of a specific treatment and poor prognosis of LC, the typical leukemia treatments are generally used to improve skin lesions 13. Based on the bone marrow status, the treatment can be varied in different patients. For examples, in patients not involved in bone marrow, an intensive AML chemotherapy is used when there is no bone marrow involvement, but LC shows resistance to the treatment, the approach is to use the total skin electron beam (TSEB) therapy to ensure the maximal control of the disease. If the bone marrow status indicates AML, then, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is an excellent therapeutic approach 14. However, using HSCT for older patients can result in severe inhibition of hematopoiesis. Therefore, in these patients, 5-azacytidine (5-Aza), a maintenance therapy, is a useful treatment option. 5-Aza, which is a hypomethylating agent, can regulate gene expression by suppressing DNA methylation 15. Cytarabine and fludarabine are two significant components of the chemotherapy regimens used in the treatment of leukemia and lymphoma. These chemotherapeutic agents prevent DNA synthesis by binding to cytosine bases and ribonucleotide reductase/ DNA polymerase 16,17.

Katagiri and colleagues reported a woman with MS (myeloid sarcoma) and LC associated myelodysplastic syndrome. For the patient was prescribed 5-Aza following the induction therapy with daunorubicin and cytarabine. Consequently, LC vanished after these treatments 15. Similarly, in 2017, Kara and colleagues used azacitidine therapy for a case of LC with AML-M4, but after the refractory to the therapy and the development of cutaneous, salvage therapy with cytarabine was proposed 18. Therefore, in patients with relapsed and refractory AML, salvage chemotherapy regimens should be utilized. These regimes are as follows: EMA-86 (Mitoxantrone, Cytarabine, and Etoposide), FLAD (Fludarabine, Cytarabine and Liposomal daunorubicin), FLAM (Flavopiridol, Cytarabine and Mitoxantrone) and FLAG (fludarabine, cytarabine and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor) 19. Our case was unique for the following reasons:

- Patient has acute myeloid leukemia (AML-M5)

- Cutaneous

- Complete remission of LC after salvage therapy

Our case accentuates the importance of clinical diagnosis and suggests considering LC patients as refractory leukemia for the use of salvage chemotherapy regimens.

Conclusion

Due to the absence of standard guidelines for the management of treatment, LC has a poor prognosis. In this study, the choice of appropriate treatments and the continuous follow-up have led to an improvement in leukemia cutis lesions.

Abbreviations

AML: acute myeloid leukemia

AMOL: acute monocytic leukemia

BMA: bone marrow aspiration

BMB: bone marrow biopsy

CAG: cytarabine, aclarubicin, and G-CSF

FAB: French-American-British

FLAG: fludarabine, cytarabine, and G-CSF

HSCT: Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

LC: Leukemia cutis

MS: myeloid sarcoma

TSEB: total skin electron beam

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Mehrdad Payandeh & Afshin Karami: Literature search, Clinical studies, Data acquisition, Data analysis; Afshin Karami: Manuscript preparation, Manuscript review, Guarantor; Noorodin Karami: Concepts, Design, Definition of intellectual content, Literature search, Manuscript editing; Soode Enayati, & Mehrnoush Aeinfar: Manuscript editing, Literature search. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

-

Cho-Vega

J.H.,

Medeiros

L.J.,

Prieto

V.G.,

Vega

F..

Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol.

2008;

129

(1)

:

130-42

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Rao

A.G.,

Danturty

I..

Leukemia cutis. Indian J Dermatol.

2012;

57

(6)

:

504

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Seok

D.K.,

Kee

S.Y.,

Ko

S.Y.,

Lee

J.H.,

Kim

H.Y.,

Kim

I.S.,

others

Leukemia cutis in a patient with acute monocytic leukemia diagnosed simultaneously with hepatocellular carcinoma: A case study. Oncol Lett.

2013;

6

(5)

:

1319-22

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Vilaça

S.,

Rosmaninho

A.,

Amorim

I.,

Selores

M..

leukemia cutis: first clue for an unsuspected diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol.

2012;

66

(4)

:

AB55

.

-

Creelan

M.,

Nair

M.,

Filicko-O'Hara

M.A..

68 Year-old Woman With Leukemia Under Her Skin. Med Forum.

2008;

10

(1)

:

9

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Cibull

T.L.,

Thomas

A.B.,

O'Malley

D.P.,

Billings

S.D..

Myeloid leukemia cutis: a histologic and immunohistochemical review. J Cutan Pathol.

2008;

35

(2)

:

180-5

.

PubMed Google Scholar -

Cruz Manzano

M.,

Ramírez García

L.,

Sánchez Pont

J.E.,

Velázquez Mañana

A.I.,

Sánchez

J.L..

Rosacea-Like Leukemia Cutis: A Case Report. Am J Dermatopathol.

2016;

38

(8)

:

e119-21

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Aguilera

S.B.,

Zarraga

M.,

Rosen

L..

Leukemia cutis in a patient with acute myelogenous leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis.

2010;

85

(1)

:

31-6

.

PubMed Google Scholar -

Starnes

A.M.,

Kast

D.R.,

Lu

K.,

Honda

K..

Leukemia cutis amidst a psoriatic flare: a case report. Am J Dermatopathol.

2012;

34

(3)

:

292-4

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Peña-Romero

A.G.,

Domínguez-Cherit

J.,

Méndez-Flores

S..

[Leukemia cutis: clinical features of 27 mexican patients and a review of the literature]. Gac Med Mex.

2016;

152

(5)

:

439-43

.

PubMed Google Scholar -

Sambasivan

A.,

Keely

K.,

Mandel

K.,

Johnston

D.L..

Leukemia cutis: an unusual rash in a child. CMAJ.

2010;

182

(2)

:

171-3

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Narayanan

G.,

Sugeeth

M.,

Soman

L.V..

Mixed Phenotype Acute Leukemia Presenting as Leukemia Cutis. Case Reports in Medicine.

2016;

2016

:

1298375

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Whittaker

S..

Cutaneous lymphomas and lymphocytic infiltrates. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology.

2010;

1

:

1-64

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Bakst

R.L.,

Tallman

M.S.,

Douer

D.,

Yahalom

J..

How I treat extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia. Blood.

2011;

118

(14)

:

3785-3793

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Katagiri

T.,

Ushiki

T.,

Masuko

M.,

Tanaka

T.,

Miyakoshi

S.,

Fuse

K.,

others

Successful 5-azacytidine treatment of myeloid sarcoma and leukemia cutis associated with myelodysplastic syndrome: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore).

2017;

96

(36)

:

e7975

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Lamba

J.K..

Genetic factors influencing cytarabine therapy. Pharmacogenomics.

2009;

10

(10)

:

1657-74

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Shao

J.,

Zhou

B.,

Chu

B.,

Yen

Y..

Ribonucleotide reductase inhibitors and future drug design. Curr Cancer Drug Targets.

2006;

6

(5)

:

409-31

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kara

A.,

Ak\in Belli

A.,

Karakuş

V.,

Dere

Y.,

Kurtoğlu

E..

A Case of Leukemia Cutis with Acute Myeloid Leukemia on Azacitidine Therapy. Turk J Haematol.

2017;

34

(2)

:

192-3

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Ramos

N.R.,

Mo

C.C.,

Karp

J.E.,

Hourigan

C.S..

Current approaches in the treatment of relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Med.

2015;

4

(4)

:

665-95

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar

Comments

Downloads

Article Details

Volume & Issue : Vol 6 No 1 (2019)

Page No.: 2970-2973

Published on: 2019-01-30

Citations

Copyrights & License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Search Panel

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Search for this article in:

Google Scholar

Researchgate

- HTML viewed - 11097 times

- Download PDF downloaded - 1118 times

- View Article downloaded - 0 times

Biomedpress

Biomedpress