Abstract

Background: Primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) are malignant soft tissue tumors of neuroepithelial origin with an aggressive nature and associated with early disseminated metastasis, resulting in poor prognosis. It occurs more frequently in men of age < 35 years, and in several parts of the body, such as pulmonary tract, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, and/or neck. Orbital location is infrequent and has been reported in less than 20 cases in the English literature so far.

Case presentation: In this paper, we report our experience with a 77 year-old man who was referred with a 2.8 cm mass in the superior-anterior quadrant of his left eye for 2 weeks prior to admission, as well as having a 15-kg weight loss during the past six months. The patient developed rapidly progressive visual loss, decreased eye movements, and conjunctivitis within a week. Thus, the patient underwent orbitotomy and the results of histological examination and immunohistochemistry showed an orbital PNET. Metastasis to frontal sinuses and ethmoid sinuses were also discovered. The patient passed away before referral to the oncologist.

Conclusion: This report confirms the highly aggressive nature of PNET and reports its rare occurrence in orbital cavity.

Introduction

Primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) are malignant tumors of neuroectodermal origin, in the Ewing’s sarcoma (EWS) family, and is categorized into central and peripheral PNET based on the presenting site1. Due to the low incidence, there is little data available about the exact epidemiology and management guidelines. PNET predominantly occurs in male patients, aged <35 years2. The disease is aggressive with a poor prognosis, mainly due to early disseminated metastasis at the time of diagnosis3.

Peripheral PNETs may occur at different locations, such as pulmonary tract4, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, or neck3, but orbital PNET has been very rarely reported5, 6, 7. Furthermore, PNET is considered a disease of children and adolescence, and has rarely been reported in adults8, 9, 10. Accordingly, orbital PNET in adults is an extremely rare phenomenon. Herein, we present our experience with a rapidly progressive orbital PNET in a 77-year-old male patient who had a very poor prognosis and died 1 week after surgery before starting any treatment.

Case presentation

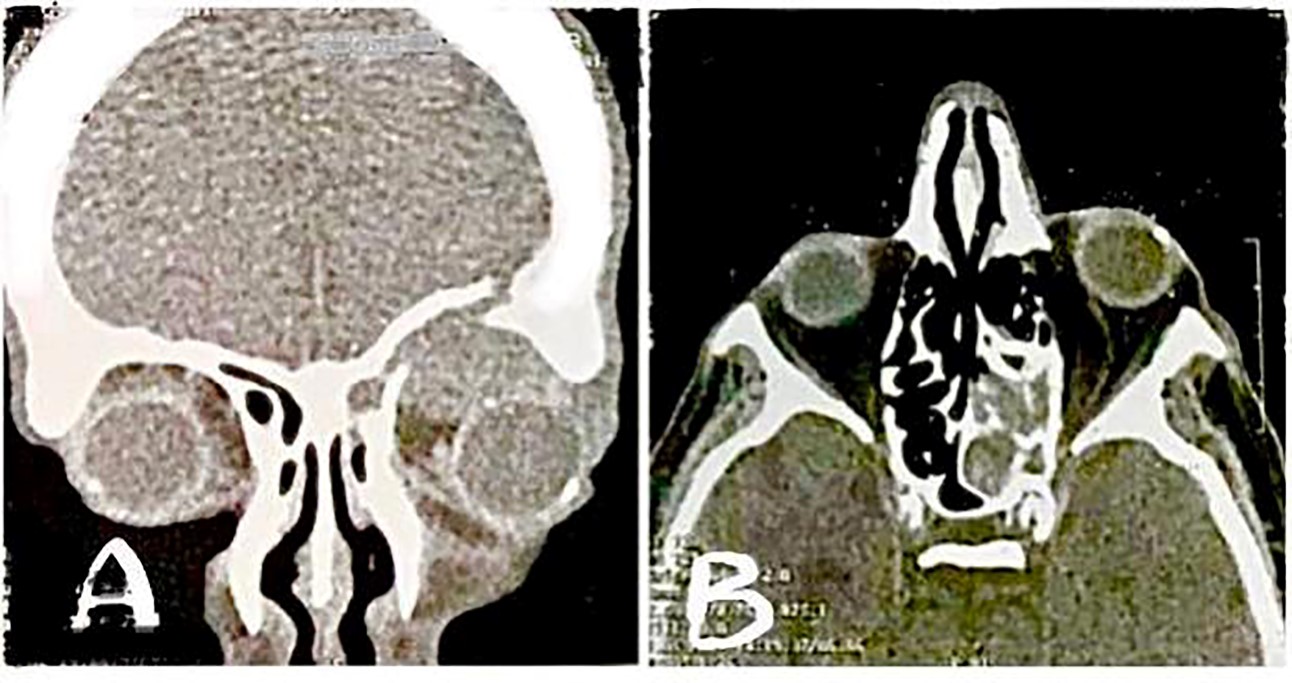

A 77-year-old man presented with a rigid mass above his left eye for one month before admission (Figure 1). The patient reported a positive history of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hypertension, as well as current smoking. The patient reported a 15-kg weight loss during the last 6 months and seemed cachectic on admission. Two weeks before referral, the patient felt a solid mass on the upper part of his left eye without pain, which caused proptosis and limitation of eye movements for the patient. In the lab data, he had a high fasting blood sugar of about 200 mg/dL, and the rest of serum measurements were within the normal range. An expert ophthalmologist visited the patient and recorded a visual acuity of 20/20 for the patient. The results of the computed tomography (CT) scan reported a mass in the anterior section of the eye with involvement of ethmoid and frontal sinuses, in addition to erosion in the upper rim of the orbit (Figure 2). These results suggested metastasis as the main diagnosis in this patient. The patient was referred with the results of CT scan after one week and on the second examination, he had severe limitations in eye movement with severe proptosis and hypoglobus, and his visual acuity reached 2/20, although he reported no pain.

Due to the rapid disease progression, the ophthalmologist decided to perform orbitotomy for resection of the orbital mass, before taking images for revealing the main tumor site that caused metastasis to the eye. Therefore, the patient underwent orbitotomy, during which biopsies were taken from the sinuses for histologic assessment. The orbital roof was fractured, the frontal sinuses and ethmoid sinus were involved, but the cavernous sinus was not. Gross examination of the resected orbital mass revealed multiple pieces of creamy brown soft tissue, measuring 2.2 × 2 × 1.8 cm in aggregate. For microscopic examination, the 10% neutral buffered formalin-fixed tissue fragment was embedded in paraffin, and sections were stained with hematoxylin & eosin. Histopathological examination of the tumor revealed well-defined solid cystic neoplastic tissue composed of sheets of undifferentiated tumor cells with monomorphic large round vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm with areas of necrosis and frequent mitosis (50 mitoses per 10 high-power field), suggesting small round cell tumor (Figure 3).

Sections were studied by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and antibodies were applied synchronously with appropriate positive control slides. The results of IHC showed the section was positive for FLI-1 (Figure 4), as well as epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), Vimentin, CD34, and CD99 (Figure 5 ; A-D), but was negative for leukocyte common antigen (LCA), CD3, CD79a, CD30, CD31, CDI38, Cytokeratin (CK) AE1/AE3, P63, S100, Human Melanoma Black (HMB)-45, Desmin, Myeloperoxidase (MPO), CD117, Chromogranin, and Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). Synaptophysin was patchy and weakly positive in tumor cells, and Ki67 was positive in about 70% of tumor cells. Based on these findings, diagnosis of orbital PNET was confirmed.

The patient was discharged one day after surgery. One week after discharge from hospital, he was re-admitted for a high blood sugar (BS) level (600 mg/dL) with suspicion of diabetic ketoacidosis. The patient’s BS was controlled during admission, and he was discharged after one day. The day after discharge, the patient passed away, and we could not determine whether the patient had any metastasis in other parts or find the origin of the tumor, as the patient passed away before referral to an oncologist (and two weeks after his first referral to our center). The main factors of the patient expiring included the age of patient, uncontrolled DM, cachexia, and aggressive nature of disease.

Discussion

In this paper, we reported a male patient aged 77 years old who had orbital mass for one month and was diagnosed with orbital PNET after orbitotomy. This case is very rare, as PNETs are generally considered a disease of childhood and adolescents, with only a few cases having been reported in adults8, 9. In addition, orbit is an infrequent location for PNET with less than 20 cases reported in the English literature so far, most of which were reported in children7 as there have been very few cases in adults. In Table 1, we tried to summarize the 8 reported adult cases with orbital PNET thus far documented in the English literature. Comparison of the patient’s conditions with the previously reported cases showed that our patient was the oldest of all cases, with the average age of the cases reported to be about 55 years old. In addition, our patient was a heavy smoker with several underlying diseases, including hypertension, uncontrolled DM, and smoking, which could be related to the rapid disease progression. However, the cases reported in the literature (summarized in Table 1) did not mention the underlying diseases. One of the cases described by Choktaweesak et al.6 developed PNET two days after cataract surgery, but this was not the case in our patient and the authors did not explain the reason for any association between these two conditions.

| First authors | Title | Year published | Patient’s Age | Location | Positive IHC markers | Intervention | Metastasis | Outcome at follow-up |

| Shuangshoti et al . 11 | Primary intraorbital extraocular primitive neuroectodermal (neuroepithelial) tumour | 1986 | 52 | Right eye, lateral side | GFAP | Surgery ad radiotherapy | No | alive after 6 months |

| Kiratli et al . 12 | Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the orbit in an adult: A case report and literature review | 1999 | 28 | Right eye, lateral side | NSE, vimentin | Excisional biopsy of the tumor en bloc | No | alive after 15 months |

| Hyun et al . 13 | Metastatic peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) masquerading as liver abscess: a case report of liver metastasis in orbital PNET | 2002 | 37 | Retrobulbar, intraconal |

NSE, S100, CD57|

Resection and adjuvant chemoradio-therapy

|

Yes (liver; three years after treatmnet)

|

alive after 35 months

|

|

| Choktaweesak et al . 6 | Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor of the Orbit in Adults: A Case Series | 2011 | 72 | Right eye, two days after cataract surgery | CD99, vimentin, FLI-1 | Radiotherapy and chemotherapy | No | Recurrence after 9 years, died of aspiration pneumonia |

| Choktaweesak et al . 6 | Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor of the Orbit in Adults: A Case Series | 2011 | 65 | Left eye proptosis | CD99, S100, vimentin, synaptophysin, BCL2 | Radiotherapy and chemotherapy | No | No signs of recurrence after 2 years, died after 6 years of another cause |

| Choktaweesak et al . 6 | Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor of the Orbit in Adults: A Case Series | 2011 | 61 | Right eye proptosis | neurofilament, CD56, CD99, and synaptophysin. | Incomplete chemotherapy | No | Recurrence after 2 years, alive after 9 years |

| Choktaweesak et al . 6 | Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor of the Orbit in Adults: A Case Series | 2011 | 62 | Right eye buldging, recurrenc after 25 years | CD99 | Orbital exploration and tumor removal and incomplete chemotherapy | No | No recurrence after 9 years |

| Choktaweesak et al . 6 | Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor of the Orbit in Adults: A Case Series | 2011 | 65 | Left eye proptosis over 2 weeks | weakly positive for CD99 | Systemic chemotherapy and radiation with limited response | Yes | Died 16 months later due to metastasis |

Our patient had no pain, despite significant proptosis and limitation of eye movements. Some of the cases reported previously also reported no pain6, while some patients reported severe orbital and facial pain6, 13. On the other hand, the severe cachexia and weight loss reported in our patient was not mentioned in previous cases. An important clinical observation in our case was the involvement of ethmoid and frontal sinuses, in favor of metastasis; however, sinus involvement had not been described in previous cases. Also, we observed a rapid progression of the orbital mass in this patient, which resulted in deterioration of the patient’s visual acuity and eye movement for one week. Such an aggressive and rapidly progressive nature of the disease had not been reported in the previous cases. Only 1 of the cases described by Choktaweesak et al.6 developed left eye proptosis over two weeks; that patient died 16 months after treatment due to metastasis. The disease progression in that case seemed slower than that of ours, although we do not exactly know about the time of initiation in our case and only know that he was expired two weeks after his first referral to us. Unlike our case, some other cases did not show rapid progressive disease, such as the 4th case of orbital PNET reported by Choktaweesak and colleagues, who had a recurrence of orbital PNET from 25 years prior, which was successfully removed without any recurrence in the 9-year follow-up (34 years after first diagnosis)6. The other cases also reported a slow progressive nature6, 13, 12, 11. Previous reports have shown metastasis of orbital PNET to liver13 and another 2 cases of metastasis of orbital tumor- one shortly after treatment, which resulted in the patient’s death, and the other after 25 years with good prognosis6. Thus, it seems that the disease progression of the reported cases have been remarkably diverse.

The imaging results in our patient showed erosion in the upper rim of the orbit, which suggested that the mass was metastatic, while the cases presented previously have reported negative erosion in CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)6, 13, 12, 11, which was another unique condition in our case4. In our case, FLI-1, EMA, Vimentin, CD34, and CD99 were positive, and Ki67 was very high, while synaptophysin was weekly positive. We did not perform chromosomal analysis in our study as the current evidence suggests that genetic confirmation is only required in unusual variants14, and we found no light microscope evidence of rosettes. As suggested, combination of CD99 and FLI-1, observed in about 70-100% of cases, is very important for diagnosis of EWS or PNET4, 15; both of these markers were positive in our case. The 5 cases reported by Choktaweesak and colleagues were all positive for CD996, similar to our present case, but CD99 (which plays an important role in cellular adhesion and proliferation) is not a specific marker for PNET and can be positive in other small round cell tumors as well16. Positivity of FLI-1 is one of the most important markers in PNET; FLI-1 is a nuclear transcription factor involved in tumorigenesis and cellular proliferation. The specific translocation of ES/PNET results in production of EWS-FLI-1 protein, which is highly specific for the diagnosis of ES/PNET17, 18. However, it can also be positive in other conditions, such as Merkel cell carcinoma, synovial sarcoma, hemangiomas, angiosarcoma, epitheliod hemangioendothelioma, and glomous tumors, which make diagnosis difficult17, 19. Other small blue round cell tumors, including rhabdomyosarcoma, EWS, lymphoma, neuroblastoma, and metastatic retinoblastoma, are considered to be important differential diagnoses of orbital PNET16.

Due to the rapid disease progression, orbitotomy and tumor resection was performed for the patient, but the patient expired early after preparation of the results of the histopathological examination and did not receive specific treatment for PNET. In most of the previously described cases, treatment of orbital PNET included chemotherapy and radiotherapy6, 7, while some patients discontinued chemotherapy due to its adverse events and recurrence was reported after complete or incomplete treatment (Table 1). In our case, the patient did not make it to oncological consult and treatment. Due to the low number of cases with orbital PNET, much is still to be elucidated about the best treatment for these patients.

Conclusions

The present case is the 9th reported case of adult orbital PNET and the oldest patient ever reported. Metastasis is suggested as a rare finding in orbital PNET, but our patient had metastasis in the sinuses and died soon after orbitotomy, before he could receive adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. The few cases reported with adult orbital PNET in the literature limits a definite conclusion about the clinical progress and the most appropriate treatment for these patients. Yet, this report emphasizes an occurrence of orbital PNET in adults, particularly an elderly, presenting with orbital mass, in order to diagnose and treat the patient on time.

Abbreviations

BS: Blood sugar

CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen

CK: Cytokeratin

CT: Computed tomography

DM: Diabetes mellitus

EMA: Epithelial membrane antigen

EWS: Ewing’s sarcoma

HMB: Human Melanoma Black

LCA: Leukocyte common antigen

MPO: Myeloperoxidase

PNETs: Primitive neuroectodermal tumors

Acknowledgments

This article was derived from a research project approved by the Esfarayen University of Medical Sciences, which was conducted with the financial support of this university. The researchers would like to express their gratitude to the University Research Council and all patients, who participated in this study.

Author’s contributions

BG: Concepts, Clinical studies, Data acquisition, Manuscript editing, Manuscript review

MA: Concepts, Literature search, Clinical studies, Data acquisition, Manuscript preparation

AD: Concepts, Data acquisition, Manuscript review

FR: Data acquisition, Manuscript preparation

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki. Written and verbal informed consent for patient information and images to be published was provided by the patient.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

-

Ellis JA, Rothrock RJ, Moise G, McCormick PC, Tanji K, Canoll P, et al. Primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the spine: a comprehensive review with illustrative clinical cases. Neurosurg Focus.

2011;

30

(1)

:

E1

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Smoll NR. Relative survival of childhood and adult medulloblastomas and primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs). Cancer.

2012;

118

(5)

:

1313-1322

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Windfuhr JP. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the head and neck: incidence, diagnosis, and management. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol.

2004;

113

(7)

:

533-543

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Weissferdt A, Moran CA. Primary pulmonary primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET): a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of six cases. Lung.

2012;

190

(6)

:

677-683

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Das D, Kuri GC, Deka P, Bhattacharjee K, Bhattacharjee H, Deka AC. Primary primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the orbit. Indian J Ophthalmol.

2009;

57

(5)

:

391

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Chokthaweesak W, Annunziata CC, Alsheikh O, Ng JD, Wilson DJ, Mansoor A, et al. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the orbit in adults: a case series. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg.

2011;

27

(3)

:

173-179

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Romero R, Castano A, Abelairas J, Peralta J, Garcia-Cabezas MA, Sanchez-Orgaz M, et al. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumour of the orbit. Br J Ophthalmol.

2011;

95

(7)

:

915-920

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Andrei M, Cramer SF, Kramer ZB, Zeidan A, Faltas B. Adult primary pulmonary primitive neuroectodermal tumor: molecular features and translational opportunities. Cancer Biol Ther.

2013;

14

(2)

:

75-80

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Mohsin R, Hashmi A, Mubarak M, Sultan G, Shehzad A, Qayum A, et al. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor/Ewing's sarcoma in adult uro-oncology: A case series from a developing country. Urol Ann.

2011;

3

(2)

:

103

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Baldini EH, Demetri GD, Fletcher CD, Foran J, Marcus KC, Singer S. Adults with Ewing's sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor: adverse effect of older age and primary extraosseous disease on outcome. Ann Surg.

1999;

230

(1)

:

79

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Hyun CB, Lee YR, Bemiller TA. Metastatic peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) masquerading as liver abscess: a case report of liver metastasis in orbital PNET. J Clin Gastroenterol.

2002;

35

(1)

:

93-97

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Kiratli H, Bilgiĉ S, Gedikoğlu G, Ruacan Ş, Özmert E. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the orbit in an adult: A case report and literature review. Ophthalmology.

1999;

106

(1)

:

98-102

.

View Article Google Scholar -

Shuangshoti S, Menakanit W, Changwaivit W, Suwanwela N. Primary intraorbital extraocular primitive neuroectodermal (neuroepithelial) tumour. Br J Ophthalmol.

1986;

70

(7)

:

543-548

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Tsokos M, Alaggio RD, Dehner LP, Dickman PS. Ewing sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor and related tumors. Pediatr Dev Pathol.

2012;

15

(1)

:

108-126

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Ahmed S, Hashmi SN. Immunohistochemical detection of FLI-1 protein expression in Ewing Sarcoma/ peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumour: A study of 50 cases. J Pak Med Assoc.

2016;

66

(10)

:

1296-1298

.

-

Sharma S, Kamala R, Nair D, Ragavendra TR, Mhatre S, Sabharwal R, et al. Round cell tumors: classification and immunohistochemistry. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol.

2017;

38

(3)

:

349

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Folpe AL, Chand EM, Goldblum JR, Weiss SW. Expression of Fli-1, a nuclear transcription factor, distinguishes vascular neoplasms from potential mimics. Am J Surg Pathol.

2001;

25

(8)

:

1061-1066

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Llombart-Bosch A, Navarro S. Immunohistochemical detection of EWS and FLI-1 proteins in Ewing sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumors: comparative analysis with CD99 (MIC-2) expression. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol.

2001;

9

(3)

:

255-260

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar -

Louati S, Senhaji N, Chbani L, Bennis S. EWSR1 Rearrangement and CD99 Expression as Diagnostic Biomarkers for Ewing/PNET Sarcomas in a Moroccan Population. Dis Markers.

2018;

2018

:

7971019

.

View Article PubMed Google Scholar

Comments

Downloads

Article Details

Volume & Issue : Vol 7 No 10 (2020)

Page No.: 4058-4065

Published on: 2020-10-31

Citations

Copyrights & License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Search Panel

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Google Scholar

Pubmed

Search for this article in:

Google Scholar

Researchgate

- HTML viewed - 3679 times

- Download PDF downloaded - 705 times

- View Article downloaded - 0 times

Biomedpress

Biomedpress